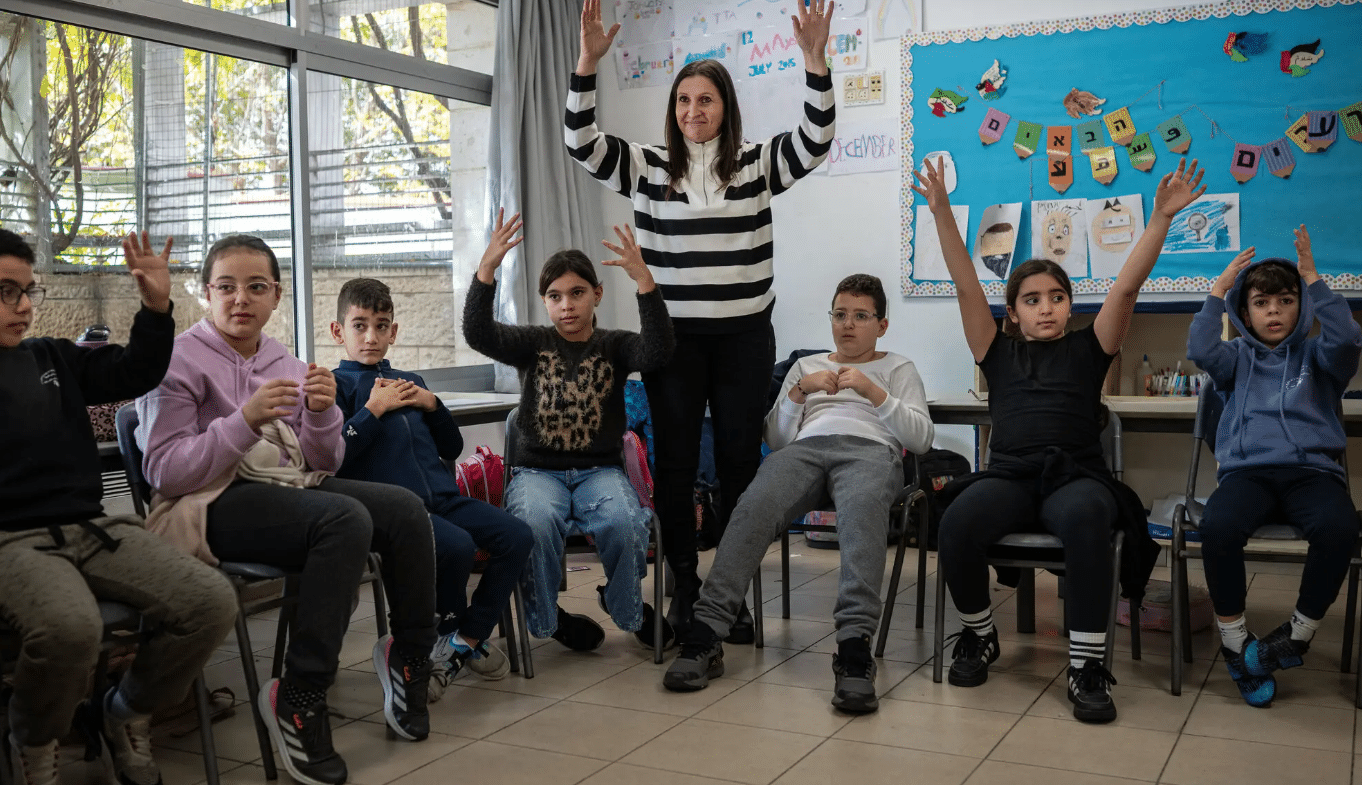

In a classroom decorated with Hebrew and Arabic letters, a group of third graders — their eyes closed, their hands placed facing up on their laps — took a deep breath in unison.

“And exhale,” a teacher told them.

The students, a mix of Jews and Arabs, attend Max Rayne Hand in Hand School in Jerusalem, one of six such bilingual institutions in Israel dedicated to the proposition that Israelis and Palestinians can learn and live together in peace. On a recent day this month, soon after a temporary cease-fire in Gaza collapsed and the prospect for peace seemed more distant than ever, the students were meditating.

If regional peace seemed momentarily unobtainable, at least they could try for inner calm.

Schools across Israel, most of them divided along lines of religion and language, are struggling with how to help students cope emotionally during the deadliest conflict in a generation. At Hand in Hand schools, where every class has two teachers — a Hebrew speaker and an Arabic speaker — the conversation about the Oct. 7 terrorist attacks and the subsequent war unfolding in Gaza sounds markedly different than in other schools.

[The New York Times Report continues]

That has only strengthened the resolve of the schools’ leaders. “It’s possible to be together, it’s preferable to be together, and it’s also the right thing to do,” said Gezeel Jarroush Absawy, the principal of the Hand in Hand elementary school in Haifa.

To that end, the schools emphasize processing individual and generational trauma. They present history through the lenses of both Israelis and Palestinians, and foster relationships between Arabs and Jews in childhood in the hope that they can extend into adulthood.

“We need to be friends with each other and not fight,” one student at the Jerusalem school said in Arabic. “We can live in peace,” said another in Hebrew. “Even older people and children can accept each other so we can be safe,” said another Arabic-speaking student.

The schools’ approach differs sharply from that of many schools in Israel, where a far-right government is pushing a nationalist curriculum. And it is particularly different from that in the Hamas-controlled schools that operated before the war in Gaza, where by law all classrooms were segregated by gender, girls were required to wear religious dress and textbooks did not recognize the state of Israel.

[The New York Times Report continues]

Like their children’s teachers, the parents worried about what would happen to their fragile community in the immediate aftermath of Oct. 7. When Arab and Jewish parents sat down together for the first time after the attack, Ms. Ben-Nun and Ms. Karkabi asked everyone to share why they had chosen to attend the session. “We came to listen,” they recalled parents saying one after another.

The parents said they were exhausted, devastated, anxious and angry. But they also expressed a shared vision of the future, in which Israelis and Palestinians would be real partners.

“The complexity is still there, and I expect it to be there,” Ms. Karkabi said. “We don’t always agree with each other, but we hear each other.”

But everything at Hand in Hand is not meditation and deep conversation. Blink and it is an ordinary school. Students fumble with their backpacks, do gymnastics at recess and race to class at the song that marks the next period.

[The New York Times Report continues]

Along the way, Ben’s father drove them past apartment buildings with Israeli flags displayed outside, and another with a sign that read, “Give Peace A Chance.” Ben, 9, talked cogently about his anxiety about the war, and how his favorite subject recently switched from science to art.

“My best friend is Arab,” he said as he looked out the car’s window. “It feels fun, a religious Jew being friends with an Arab.”

The boys like going to the library together and playing soccer. But, Ben added, things are also stressful.

“It’s kind of hard to believe that there’s literally people getting killed right now,” he said as his father pulled up to the front of the school. “And here, it’s just like, chill. Another normal day.”

Arriving at school, Ben grabbed his bag and hopped out of the car. The boy’s father gave him a kiss goodbye on the head, and Ben ran into the school — hoping to find his best friend.